“DOC”

- Aug 14, 2016

- 11 min read

Updated: Jul 21, 2022

The picture is larger on the page, to match the man’s outsize personality. This is what Scott Huston looked like during my years of study with him at the College-Conservatory of Music at the University of Cincinnati. Doc passed away in 1991; my last lesson with him was several years earlier. I may have been one of his final doctoral students, as I finished up my DMA requirements in 1988. Doc came to my hooding ceremony; I still have a picture of the two of us at home in the family photo albums.

Many people fondly remember special teachers, those individuals who especially pointed the way to knowledge and understanding. These are the people who cared deeply about the subject matter at hand, but had even greater passion for their students. They were the ones who provided the extra help when it was needed, the “lifeline,” as Doc would say, to keep us from drowning! Scott Huston’s personality was king-sized and seemingly ferocious at times, but his enthusiasm was undeniable. His intensity was wedded to a deep love for music and the people who shared that love with him. Doc was a man who cared deeply about his students and wanted them to succeed. He also had some great insights to share with us, although we didn’t always agree with those ideas at the time!

I applied to the College-Conservatory of Music as a graduate student in 1977. Doc told me that he examined my scores and told the faculty that “I can work with this one.” That’s how I landed up in his studio. My undergraduate composition portfolio had gotten me in the door to a prestigious institution, but that was all. As one professor said: “We might accept you to CCM, but you are not getting out of here unless you can measure up to our high standards.” Fortunately, the man who took me on knew how to help his students get through the challenges that were ahead.

Masters students would work with Dr. Huston once a week in a masterclass environment at his studio. Each one of us would have a turn in the 3 hour plus class to present our work from the previous seven days. You would place your score on the piano, and Doc would begin to play through the scribble, aided only by a cup of coffee and a cigar. Yes, he was a smoker; cigars were the poison of choice when he was feeling particularly fine. Pipes were also acceptable; he told me that he only smoked cigarettes on occasion, when he wasn’t feeling well.) The grand piano that was in his office was a giant ashtray; what a mess that instrument must have been years later, when the conservatory came to claim it for repair…….

I can still remember my first lesson with Scott. I brought a choral piece that I had composed as an undergraduate student, the work that demonstrated my “finest” achievement up till that point in time. My thought was simply to go in there with my best stuff and see how things stacked up. If my score didn’t make the grade, I could always pack up and go home. Doc probably figured out the strategy. He made sure that he complimented the piece first; then showed me little things to improve the score, and make life more reasonable for the singers. This was going to be a common theme in the years to come, developing the skills that enabled you to write what you need without killing your performers in the process! Challenging them was still okay, though.

From there, Doc provided me with a first assignment. With a piece of manuscript paper, he demonstrated the concept of the synthetic scale, a simple collection of pitches that were collected by the composer for use in a given work. He asked me to write a short piece for the piano, using a scale of my own derivation. This was a new sort of compositional challenge at the time; home I went to figure this out.

One week later, I was back with a short, two-page piece for piano, based on a scale of

5-6 pitches, just as assigned. It may have been the piece shown below, (see excerpt,) or one of the others that I eventually wrote at this time. I remember my attempts to incorporate more disjunct motion into my music than I had in the past, so that I might sound more “contemporary.”

Up the music went on the piano stand, and Doc began to play. He didn’t grab every note, but his accuracy overall was most impressive. When the piece was over, he paused, looking the pencil score over one more time. He turned to me, flashed one of those terrific “you got it!” Huston smiles and shook my hand. Doc had seen progress, the kind he hoped would happen from this simple assignment. From there, he did the same thing as the week before, commenting on what was on the page in a very positive fashion, adding suggestions for me to consider. “Go out and write another one or two short pieces for next week!”

I was higher than a kite. Lessons were on Friday afternoons; what a way to go home for the weekend! My first department composition recital appearance that same semester consisted of five short pieces for piano, all based on the various pitch collections that I had developed on my teacher’s instructions. I played them myself. Encouraging comments came my way from faculty and colleagues; perhaps I could survive in this conservatory environment, after all.

Doc was pleased enough to give me a new assignment: a poem to set for baritone and chamber orchestra. The text was for this new project was written by a faculty member at Miami University; he had probably approached Doc about setting the text to music himself. Scott probably didn’t have time to do this, so he created an opportunity for one of his students instead, a move that I use with my own students to this day. I eventually met the poet, learned about the background of his text and wrote a short, seven-minute piece that one of the CCM orchestras played in a reading session. Early successes like this fueled my passion to continue.

Lessons for that piece also showed a sometimes annoying but still comic side of Doc’s teaching style. He would always “sing” the vocal lines as he played your accompaniment. His over-the-top, croaking vocal performances were enough to make even the strongest constitution cringe! But this was not mockery; it was pure enthusiasm. As awful as it sounded, it gave him the opportunity to show you where your text setting worked, and where it needed help.

Not all of my experiences with creativity were this exhilarating, of course. My path to greater compositional prowess also produced a number of truly mediocre works. My style of writing was expanding to the more pantonal style that was expected of young composers at that time. Doc also said that I needed to start writing away from the piano, to free myself of its influences. I still remember the times where six measures of bad music was a good week. But Doc was endlessly patient; he knew that I would work through these issues and I did. Over two degree programs, I slowly developed the craft that still serves me today.

Doc also was patient with my continuing need to write tonal music; I just couldn’t be a post-Schoenberg disciple all the time. This was especially true for my choral music and anything that I wrote for the church. My life was turning into a two-sided reality: the contemporary conservatory composer and the closet tonal composer. I could bring my tonal works into the studio on occasion; these pieces were just another opportunity to improve my craft. No other professor at the conservatory would have allowed me to do this. Heresy!

Fortunately, I experienced Doc’s larger-than-life teaching style in the composition studio. Had I had first encountered him in the classroom, I may have changed careers. It was not that his ideas were remarkably different; what he said in the classroom matched what he maintained in his studio. But his super-intense method of classroom interrogation put fear into my heart! At times, I mistook his enthusiasm for something else; I was often uncomfortable and tense in his Analytic Techniques classroom. With time, I learned to work through my difficulties and all of my other courses with him were fine. But I also decided that in the future, my classroom teaching style was going to be different. You can’t learn when you are tense, I decided. Find a way to make students feel a bit more safe in the classroom without going soft. This slight modification from my teacher’s manner has served me well over the years

Doc was a man of many opinions, usually strong ones. What do you say to a man who shouts this to a class……“Schubert was a teenager!......... And what about this sensitive piece of musical assessment: “I used to listen to Mahler…….then I grew up!”

And then there was Norman Dello Joio. Poor Norman, he probably never knew what was being said about his music in the CCM hallways, and it was probably just as well. Doc didn’t approve of his compositional technique and we knew this. So when we would see him coming down the hallway, the bogus conversations would start…….’Hey Tony, I just listened to another great piece by Norman Dello Joio! Shall I put the score aside for you? Then we would stand back and wait for the fireworks to begin!

We did learn a great deal about the composers and the pieces that Doc did admire, however and that made all the difference, as the poet Robert Frost said. I’ll never forget one of Doc’s most important questions, as we examined various significant pieces of music in his class, presented in chronological order, of course. Here was the question:

“What do you see in this piece that you haven’t seen before?”

It was a simple question, but always a good one. Art is in a constant state of evolution, as ideas change. Doc’s courses always showed you a genuine path of discovery and change. Study the amazing aspects of these new developments and consider their implications for the music in years to come. When something truly amazing happened in the score, we saw a physical reaction from our instructor: the palm of the hand would hit his forehead and produce a look of comic amazement…..it was silly and profound at the same time.

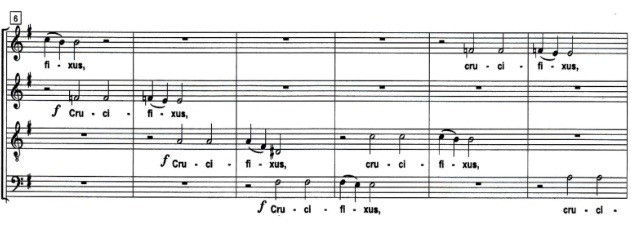

Doc presented his ideas as gospel, whether the larger world agreed with him or not. Text-painting, for example, happened a lot sooner than historians usually acknowledge. Doc would show you that the technique was really born with selected examples of Gregorian Chant, whether the Church fathers liked it or not. He would teach you that perfection in composed music was best offered in smaller, more concise pieces of music, such as the Crucifixus movement from the Bach B Minor Mass. And, oh yes we learned that we had spent our entire lives mispronouncing the title of this famous piece! Check the original Greek…..that second syllable required the hard k sound. He didn’t win a lot of converts on that point, but nothing discouraged him…..

Bach: Crucifixus, B Minor Mass

The Gospel according to Scott was a common term among the students who knew and loved him. There were many “my way or the highway” statements and opinions, but that was simply the price of admission. Accept what he had to offer and find ways to use the best of his teachings. I found many ways to accomplish this task; still do. Doc is with me in the classroom everyday; most of the time, I manage not to offend him!

Another story about my relationship with Doc: I remember a day in the cardiac care unit of Children’s Hospital in Cincinnati. My wife Joan and I had our first child, a son named Alan, who was born with multiple birth defects. The most serious issue was a weakened heart, which limited his health and development. We were living in the Dayton area at the time, and had brought our son to Cincinnati for the first of two heart surgeries. Joan and I spent hours in the cardiac care unit with Alan, as much as the limited visiting hours would provide. Doc knew about the surgery and came over to the hospital to meet our son and support us. He shouldn’t have been allowed to enter the unit, of course, but that wasn’t going to stop Scott. I still remember him walking into the ward, with that trademark Scott Huston grin, looking to play the part of the grandfather. He didn’t have this title, of course, but we didn’t tell anyone; Alan’s real grandfathers were not local. Doc visited with us that day, lifted our spirits, and then moved on to the next thing on his dance card. It was a little thing, but also a loving gesture that I will always remember.

One more memory from an earlier time….on this occasion, the grad composers weren’t being cocky. Our insecurities were showing. How were we going to make it through the requirements of the program, the recitals, dissertation, oral/written examinations, etc. And then to find a career in what seemed like a tiny market, even with a terminal degree? Doc happened to be walking by as we fretted. He didn’t say a word but kept listening. When he arrived at the elevator, he entered, turned to us and said in one of those rare moments that he employed a softer, fatherly tone: “Don’t worry. We’ll get you through.”

He was right.

How does one pay back someone who has done so much for your life’s work? In reality, it doesn’t seem possible. The best thing to honor your professor is to go out and do the same thing for the next generation of students. Help them rise to the bar: show them the secrets of the craft. Teach them to love the music that is out there, just as you do. Don’t be afraid to show your enthusiasm and your intensity. Let them know that you expect a lot of them, but in return, you will be there for them, always.

I did find one more direct way of honoring my teacher in recent years…..Doc spent a career writing music as a professional composer, but this was well before the advent of computer software. Everything was done by hand, ink on vellum. After Doc passed on, the conservatory wanted to preserve Scott’s scores in the library. In the interests of preservation, they wanted to keep the scores under lock and key and not allow them to circulate.

This decision was not satisfactory to Natalie Huston, Scott’s widow, who wanted his work to be more readily available. For years, the stalemate continued. Through a series of Christmas cards, (and later a telephone conversation) I was able to convince Natalie that modern digital technology would alleviate her fears. Students and scholars could have access to the music without damaging the original, delicate documents. Natalie passed on before the project could move ahead, and more year went by before Doc’s scores could finally return to CCM. During this time, the manuscripts were stored in cardboard boxes in the garage of one of his daughters, who also wanted to be sure that his work was safe and secure. I had a series of conversations with several Deans, the CCM library and the family and am happy to report that the scores are now part of the CCM collection. This happy turn of events took the help and cooperation of several key individuals; it meant a lot to be a strong advocate behind the scenes for these developments.

Scott Huston is one of those moving forces that enabled me to have a career in music. He always reminded us that it was a privilege to be employed in this profession, and that is still true today. Thanks to his work (and the efforts of others) I continue to be gainfully employed in my chosen area. Doc is by my side, guiding my teaching and my composing, even if he fumes at some of my ideas! One of these days we will have a most deep and stimulating conversation, the kind that I could not do when he was alive because my mind was still mush. Perhaps I will make some arguments that I could not have made back then. I may even sound a bit more intelligent and perceptive than I was back in the day. If I can do this, at least some of the time, Doc will smile and shake my hand. . . . .

Comments